Only about one-quarter of children in the United States are reaching recommended levels of physical activity for health and well-being. Furthermore, children are spending less time in nature than ever before, missing out on the physical, mental, and emotional health benefits of engaging with the natural world. Extreme heat may serve as a barrier to engaging in physical activity, while nature may be a solution to encourage safe physical activity as our world warms. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation-funded Green Schoolyards Project was a study led by Melody Alcazar of City of Austin Parks and Recreation Department and Dr. Kevin Lanza of UTHealth Houston School of Public Health to assess how trees and other green features in three elementary school parks in Austin, Texas, serving majority economically disadvantaged, Latino populations impacted heat within parks and physical activity levels of children, and how children’s connection to nature related to their social-emotional learning (SEL) skills, those that are vital to school, work, and life success.

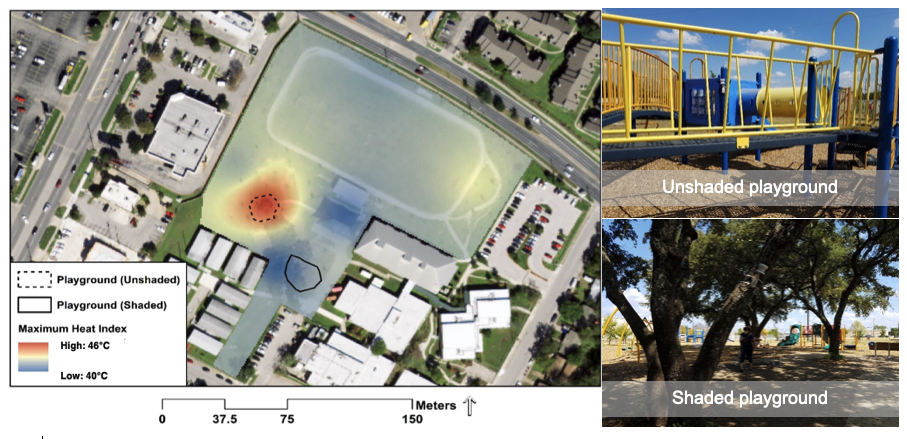

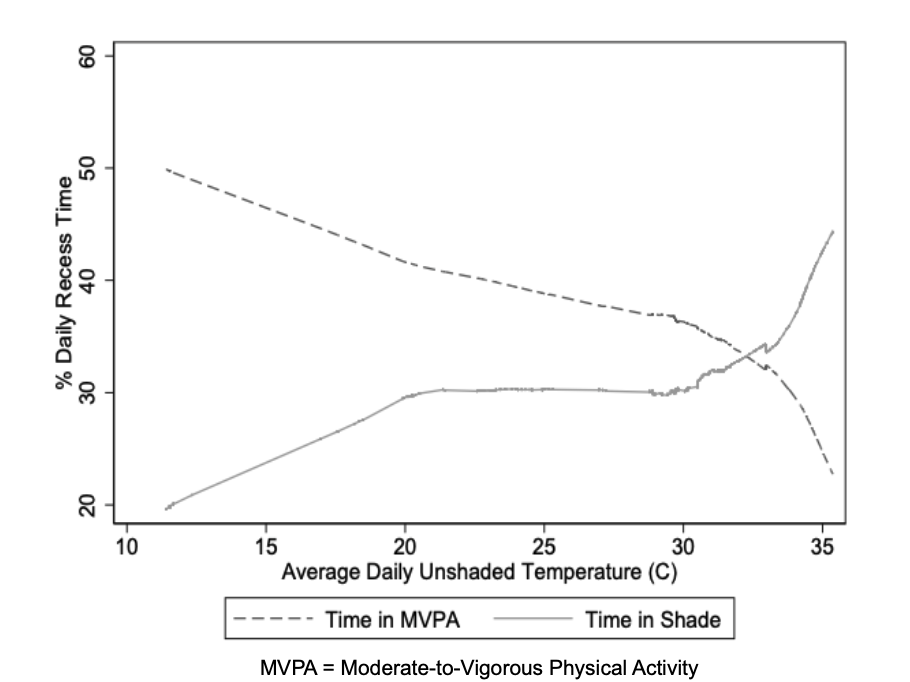

The Green Schoolyards Project provided evidence for the installation of trees and other green features as an intervention in school settings for child health. Among findings, we measured sizable differences in heat index (i.e., metric of heat that combines air temperature and relative humidity) within school parks based on land cover by installing air temperature and relative humidity sensors in each park. At one park, an unshaded playground reached about 46°C (114°F), while less than 50 meters away, a shaded playground only reached about 40°C (104°F).1 That range is the difference between “Extreme Caution” and “Danger” levels for likelihood of extreme heat disorders. Data from sensors worn by 213 children ages 8–10 during school recess revealed that as temperatures rose, children decreased physical activity and sought shade.

At and above 33°C (91°F), children were more likely to not engage in physical activity and to seek shade during school recess.2 From survey data, we found children’s psychological connection to nature was positively associated with their overall SEL skills, self-awareness, self-management, and relationship skills.3 With the study period overlapping the COVID-19 pandemic, we used systematic direct observation to show that during the pandemic, 46% fewer girls and 62% fewer boys were observed at school parks outside of school hours, relative to before the pandemic.4

Here’s a one-pager (in English and Spanish language) that summarizes the Green Schoolyards Project, its findings, and recommendations based on project findings.

1 Lanza K, Alcazar M, Hoelscher DM, Kohl III HW. (2021). Effects of trees, gardens, and nature trails on heat index and child health: Design and methods of the Green Schoolyards Project. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-10128-2

2 Lanza K, Alcazar M, Durand CP, Salvo D, Villa U, Kohl III HW. (2022). Heat-resilient schoolyards: Relations between temperature, shade, and physical activity of children during recess. Journal of Physical Activity & Health. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2022-0405

3 Lanza K, Alcazar M, Chen B, Kohl III HW. (2023). Connection to nature is associated with social-emotional learning of children. Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cresp.2022.100083

4 Lanza K, Durand CP, Alcazar M, Ehlers S, Zhang K, Kohl III HW. (2021). School parks as a community health resource: Use of joint-use parks by children before and during COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179237